CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

All text © Christopher C. Doyle, 2021. All rights reserved

All images are either © Christopher C. Doyle or used under licence as mentioned

Unauthorised duplication, recording or sharing of the contents of this chapter, or any part thereof, is strictly prohibited, unless prior permission is obtained in writing from Christopher C. Doyle. Copyright violations will be prosecuted under law and subject to claims of damages, both financial and otherwise.

You are about to take the first step on an amazing journey of exploration. An odyssey that will weave through the shlokas of the Mahābhārata, the greatest and oldest epic every written.

As we wander through the mysteries of the Mahābhārata, we will explore the different versions of the epic, from the traditional recensions to the Critical Edition, and examine the translations from different perspectives.

There are many common misconceptions about the characters, events and locations of the Mahābhārata. We will study these misconceptions in the light of what is actually contained within the Mahābhārata – what the shlokas actually say and mean, and lay to rest these fallacies once and for all. We will look at historical, archaeological and scientific evidence and explanations for what we come across – everything we discuss will be based on facts and founded in deep and extensive research.

We will get to know the people in the stories of the Mahābhārata – and you may have never heard of some of them – and explore their histories, their importance and their roles in the stories of the Mahābhārata.

We will explore the questions raised within the epic, both answered and unanswered. I will show you shlokas whose meanings and interpretations are shrouded in mystery and obscurity. You will see how difficult it is to translate and interpret some of these shlokas, and how the translations differ, even among scholars. We will explore all the translations and I will offer alternative translations as well, to give you different perspectives on the meaning of some of these shlokas.

Together, we are going to study the secrets of the Mahābhārata.

This journey will not be merely a translation of the Mahābhārata. It will be much more. It will also be an exploration of other ancient texts. We will examine the links between the people, events and stories of the Mahābhārata and other ancient texts like the Rigveda and the Puranas.

If there was ever anything in the Mahābhārata for which you wanted an explanation, chances are you will find it in this series. I can also promise you that you will learn new things and make new discoveries in the course of this series.

This will be no mere retelling or translation of the Mahābhārata. It is truly an exploration, a journey, an adventure. You and I, your partner in adventure, will together sail this vast ocean of almost one lakh shlokas with stories within stories and, together, we will decipher the secrets that lie within them.

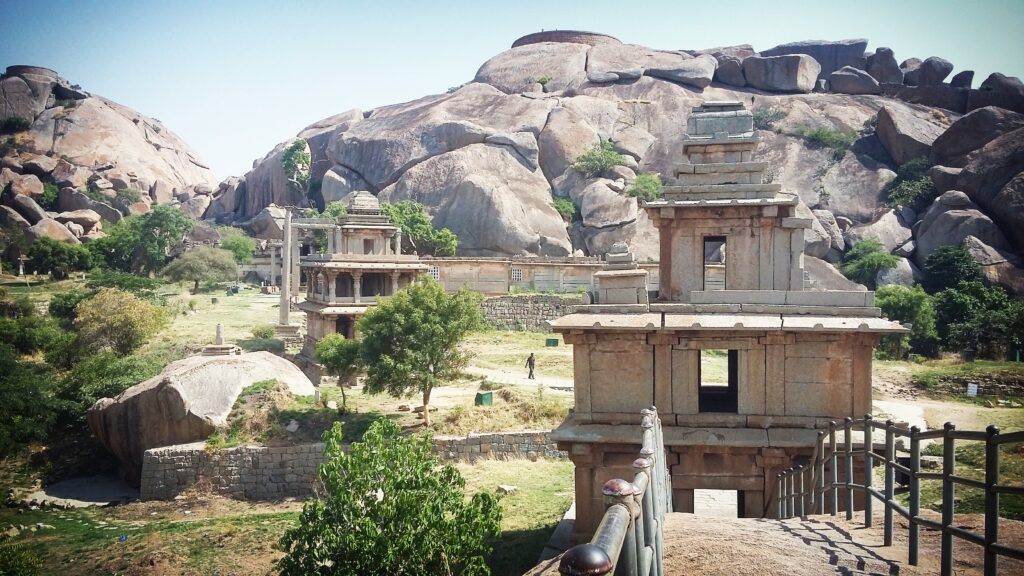

This photograph, for example, shows part of the Chitradurga fort, in Chitradurga district.

Source: Shivashankar S Bannikoppa, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

According to folk legend, Hidimba lived on Chitradurga hill. Bhima fought and killed Hidimba and this story is part of the Ādi Parva. We will explore more such stories, local legends and locations from the Mahābhārata in the course of our journey.

There is nowhere else that you will find all these facts, secrets and explore mysteries, all within one book or one series. We are going to dive deep into the Mahābhārata and explore it like it has never been explored before.

But before we begin the actual journey itself; before we dive into the one lakh shlokas of the Mahābhārata, let us study the context and background of the epic itself.

To begin with, we must understand that there is a difference between classical Sanskrit – the language of the Mahābhārata and Vedic Sanskrit – the language of the Vedas and other Vedic texts. Vedic Sanskrit had an accent which is not present in classical Sanskrit. So even I take the help of different scholars who help me with translations of Vedic Sanskrit and Classical Sanskrit.

The Mahābhārata is believed to be Itihāsa. In fact, as you will see, the Mahābhārata itself claims, several times, to be Itihāsa. Now, Itihāsa is a Sanskrit word that does not mean history. Itihāsa means: this is what happened. So the Mahābhārata is not, according to belief, a myth or a fictional account of events. It is said to be a factual account of what actually happened in the past. But we’re not going to speculate on whether the Mahābhārata actually happened or not. We’re going to focus on the epic itself, on the narration contained within these shlokas.

So, who is the author of the Mahābhārata? That is the next logical question, right?

According to tradition, the composer of the Mahābhārata is Shri Krishna Dvaipāyana Veda Vyāsa. Yes, that is his full name. And the Mahābhārata itself states that he was the composer. But, according to scholars, it is also clear from studies of the 100,000 shlokas of the Mahābhārata (or, around 75,000 shlokas in the case of the Critical edition), that it is impossible to attribute the composition of the entire epic to a single person.

We are told by scholars that the Mahābhārata that has come down to us was composed by a number of authors, each one adding sections, shlokas, stories and interpretations, until the present version of the epic was created in its full glory.

What is interesting is that this conclusion of scholars seems to be at odds with the Mahābhārata itself, which, as we shall see, insists that its sole composer is Veda Vyāsa.

But who exactly was Mahārishi Vyāsa or Vyāsadeva? Let’s find out a bit more about him, shall we?

His father was the Mahārishi Parāshara, and his mother was Satyavati.

Now, not everyone may be familiar with the story of sage Parāshara. So let me give you a little background.

Mahārishi Parāshara was the grandson of Vashista, the great Mahārishi, famous for his rivalry with King Vishwamitra. We will come across the story of Vishwamitra and Vashihta later in the Ādi Parva and I’ll tell you more about these two Mahārishis then.

But back to Mahārishi Parāshara and his family tree.

Vashishta, as we know, was a mind-born son of Brahma.

Shakti was the eldest of the 100 sons of Vashishta. His mother was Arundhati. We will hear more about Shakti in the Ādi Parva, when the Gandharva named Angārparna tells the story of the hostility between Vishwamitra and Vashishta, after being defeated by Arjun.

For now it is enough for our purpose to know that Mahārishi Parāshara was the son of Shakti and Adrishyanti. The story of Shakti and Adrishyanti is also told in the Ādi Parva and we’ll come to it in due course.

So, what do we know about Mahārishi Parāshara?

- He was the narrator of the Vishnu Purāna to sage Maitreya

- He was one of the many great sages who paid their respect to Bhishma as he lay on his bed of arrows

- He once had a discussion with King Janaka on spirituality: this story is narrated by Bhishma to Yudhishtira in the Shānti Parva, as we will see when we reach that point in the Mahābhārata.

- Nine Hymns in the Rigveda are attributed to him: Mandala I, hymns 65-73, all hymns to Agni

This photograph shows the Parāshara lake, in Himachal Pradesh, where the Mahārishi is said to have done tapasya or mediation.

Source: Ray Saudip, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This image shows the Google Earth location of the lake.

And this Google Earth image is a close up showing the height at which the lake is located.

And this is a photograph of the Parāshara cave in Panhālā, in Kolhapur district.

Source: Nilesh2 str at the English-language Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This image shows the Google Earth location of the caves.

And this Google Earth image is a close up showing the cave.

What about Vyāsa’s mother – Satyavati? If you think the name is familiar, then you are correct. She is the same Satyavati who was married to King Shāntanu, and became the mother of Chitrāngada and Vichitravirya, both of whom died at an early age. And, as we know, Vichitravirya’s widows gave birth to Pandu and Dhritarāshtra, respectively, with Vyāsa. We’ll hear this story in greater detail in the Ādi Parva.

And, in at least one respect, as you will see when we come to the story of Satyavati, Mahārishi Parāshara was responsible for setting in motion the chain of events that eventually led to the Kurukshetra war. I will explain this further when we reach that part of the Mahābhārata.

Coming back to Rishi Vyāsa, now that we know of his descent, there is another interesting fact about him, one which we learn about in the Shānti Parva. Interestingly, as we will see when we come to the story, it is narrated by Rishi Vyāsa himself, and it encompasses not only his own story, but also the story of the creation of Brahman by Nārāyana, from his navel. As part of this story, we learn that a Mahārishi named Sārasvat, also called Apāntaratamā, was created from the syllable “भोः”, which was uttered by Nārāyana. This Mahārishi was instructed by Nārāyana to arrange the Vedas. In this story, Nārāyana also tells Apāntaratamā that he will be reborn as Vyāsa and will classify and arrange the Vedas once again.

We will explore this fascinating story in more detail when we come to the Shānti Parva.

Veda Vyāsa was so named because he classified the Vedas. Veda Vyāsa is a title, rather than a name. His real name, Sri Krishna Dvaipāyana, comes from the fact that he was born on an island or dvipa – hence Dvaipāyana – and he had a dark complexion – hence Krishna.

He also composed the 18 Mahāpurānas, in addition to classifying the Vedas and composing the Mahābhārata.

There is an ancient cave in Mānā village in the Chamoli district of Uttarakhand, just a few kilometres away from the shrine of Badrinath. It is believed that Mahārishi Vyāsa composed the Mahābhārata in this cave with the help of Lord Ganesha.

This is a photograph of the cave.

And this Google Earth image shows you where the cave is located.

From the composer of the Mahābhārata, let us move to the epic itself, one of the greatest stories ever told.

The Mahābhārata is divided into 18 Parvas. The word “parva” means joint or node and is loosely translated into English as “book”. So the Mahābhārata is said to have 18 books. Each Parva is subdivided into Chapters or “adhyāya”, and each chapter consists of a number of shlokas, which are couplets or verses of two lines each.

Interestingly, the Mahābhārata itself provides two kinds of Parvas, so there are two ways of classifying the epic.

The traditional, and more commonly known, is the 18 Parva structure that I have already mentioned. These 18 Parvas are:

- Ādi Parva

- Sabha Parva

- Vana Parva

- Virat Parva

- Udyoga Parva

- Bhishma Parva

- Drona Parva

- Karna Parva

- Shalya Parva

- Sauptika Parva

- Stri Parva

- Shānti Parva

- Anushasana Parva

- Ashvamedhika Parva

- Ashramavasika Parva

- Mausala Parva

- Mahaprasthanika Parva

- Svargarohana Parva

The lesser known classification of the Mahābhārata has more almost 100 Parvas. I won’t list them all down here because we will anyway get to know about them in detail later in the Ādi Parva.

Finally, let us look at the core structure of the epic – one that has given rise to many misconceptions and misunderstandings. It is important to clear these up right at the start.

Most people, when they refer to the Mahābhārata, really mean the story of the Pāndavas and Kauravas, leading up to the Kurukshetra war. And this is, really, the core of the Mahābhārata. But it is not the Mahābhārata. There is so much more to the epic than just the story of the Kurukshetra war.

The Mahābhārata has a vast scope. It covers sweeping swathes of the history and lineage of the Kurus before finally arriving at the Kurukshetra war, which is described in some detail, as you will see. There are stories within stories, though the two principal narrators are Vaishampāyana – a disciple of Shri Krishna Dvaipāyana; and Ugrashrava, the son of Rishi Lomaharshana, who has heard the story of the Mahābhārata narrated by Vaishampāyana at the snake sacrifice of Janamejaya, the son of Parikshit and the great grandson of Arjuna the Pandava. Ugrashrava was popularly known as Sauti, and we shall be seeing more of him in Episode 2 of this series.

Scholars agree that the Mahābhārata, as it exists today, is the result of three iterations, each one building up on the previous one, enlarging the story and expanding the work.

The earliest, or original story is called Jaya and consists of 8800 shlokas. This story was later revised and expanded to 24,000 shlokas and was then called the Bhārata. The third and final expansion, called the Mahābhārata, consists of 100,000 shlokas.

It has been speculated that Veda Vyāsa composed Jaya and it was expanded to Bhārata by Vaishampāyana, at Janamejaya’s snake sacrifice, which we shall encounter soon enough. And the final version of the Mahābhārata was possibly expanded by Sauti or Ugrashrava.

Once again, this is the interpretation of respected scholars after years of research and based on existing information and manuscripts. Once again, this conclusion by scholars is repeatedly and vehemently contradicted by the Mahābhārata itself, which, as we will see, insists that its sole composer is Veda Vyāsa.

However, as I have said earlier, this series will not speculate on who composed the epic or whether the events described in it actually happened.

We are more interested in what the epic actually contains. What are the mysteries, the deep secrets that lie concealed within? And we will explore them in the course of this series.

This series will cover material from the unabridged translations of K.M. Ganguli and M. N. Dutt, encompassing the Calcutta and Bombay recensions. We will also cross reference the critical edition produced by the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute (BORI), in Pune.

With that introduction, let us wade into the waters that lie before us, going deeper and deeper, until we immerse ourselves in the immensity of this great epic.

Come with me and let us together explore the mysteries of the Mahābhārata.

Let us dive deep into the Mahābhārata and explore it like it has never been explored before.

END OF CHAPTER 1

If you enjoyed reading this chapter, then catch the rest of this series called Revealed: Mysteries of the Mahabharata, at Quest Club Gold.

All you have to do is log into your Quest Club free account and click on the Subscribe button at the bottom right hand side of the Welcome to The Quest Club page, make the payment, and your Gold membership will begin!

You can use this link to take you to the Welcome page where you can subscribe to Quest Club Gold:

Your partner in adventure,

Christopher C. Doyle